Bari Nan Rothchild

Park City, UT

barinan@gmail.com

Nordic Sport in Literature, Film, and Music

Being immersed in the world of ski jumping as parents of an athlete, my husband and I tend to geek out on the places where our family’s other passions for literature, arts, and culture overlap with the sport. (See also: “Wherever we go, there we are.” And: “When you’re holding a hammer, everything looks like a nail.”) My child chases adrenaline from the top of a ski jump; I get my dopamine hits from serendipitous connections.

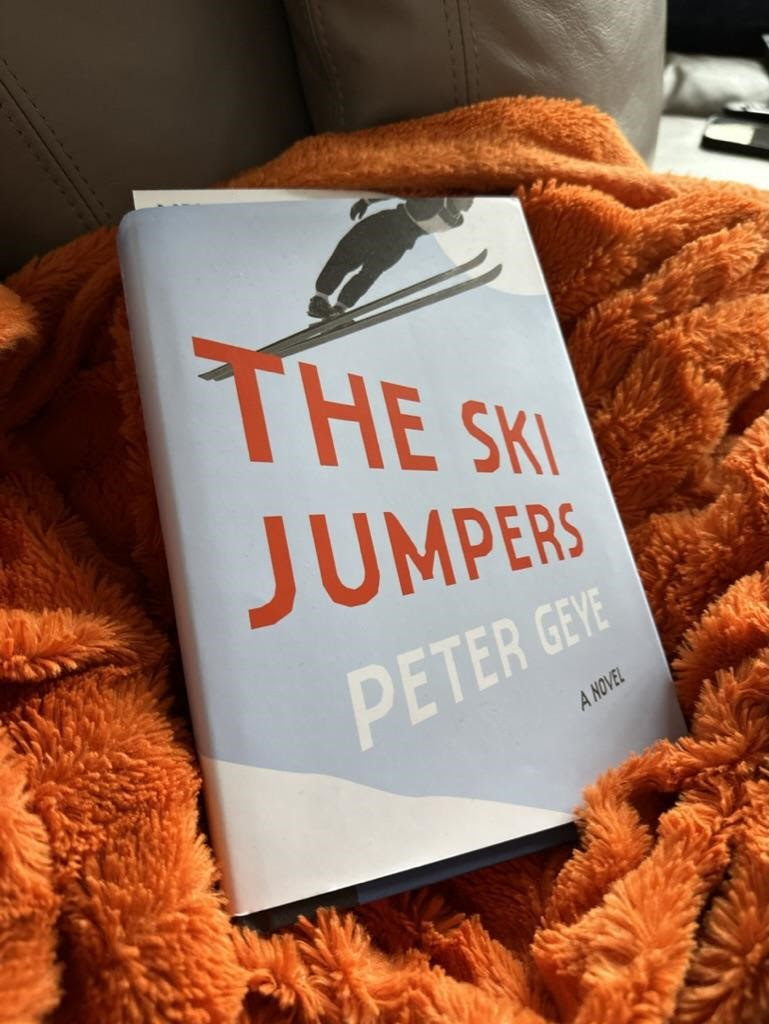

To wit: During a recent family vacation in Washington, D.C., we visited a famed bookstore/delightful rabbit-warren, Politics and Prose, where my husband found a new release that seemed to have been stocked just for us to find. The Ski Jumpers: A Novel, by Peter Geye came home with us, amidst a stack of books on politics, government, and history.

The Ski Jumpers is about fear—but not in the way the title might lead a reader to believe. Geye’s characters illustrate the way our minds can toggle between fear and fearlessness. And the ways in which fear is fickle and generally counterintuitive—we are thrilled when it abandons us, and dismayed when it inevitably arrives, unbidden. When they’re in flight, they have a sense of control that eludes them on the ground, dealing with family strife, poverty, and mental illness. Geye introduces us to Jon Bargaard, a professor and novelist who is a former ski jumper, now wrestling with family secrets, perhaps one last time, as he faces down a diagnosis of younger-onset Alzheimer’s. Simultaneously, he tries to decide if he’s courageous enough to finish writing a book about the ways the sport intertwines with his family’s complicated history. Among writers, Jon is all of us—navigating a blank page with the understanding that we create collateral damage with every word we type. In Jon’s case, the likelihood of not having the mental faculties to help mitigate that damage becomes a central question. Having seen my late mother through her end-of-life fight with dementia in her 70s, I related to the fear of the unknown Jon and his family explore with his diagnosis. And, like Jon, I have an unfinished novel I’ve been either writing or avoiding writing for the better part of a decade. But I digress.

The book opens with a sense-memory dream, Jon in flight, more than forty years after he has taken his last jump, and before long, he’s in a reckoning with a lifetime of memories that seemed destined for evaporation. Each time Geye, a former ski jumper, describes the feeling of ski jumping through his characters, he makes distinctions between one jumper’s experience of flight, and another’s. (“Your Pops always said landing was like shattering glass, but for all you learned from him, for all you believed in him, this was not your experience. Landing, for you, was an insult.”). Geye puts exquisitely specific and evocative language to the feeling of jumping—giving me a vicarious thrill of my young jumper’s experience and the reason he is in the thrall of this sport. It almost made me want to try it. Almost.

Geye is meticulous in describing the mechanics of jumping, and hews true to the jumping styles of the times spanned in the book, the latest of which is in early January 1980, at the Olympic Trials in Lake Placid. While I’d seen old-school techniques in historical photos at the Alf Engen Museum at Utah Olympic Park, I hadn’t really absorbed the specifics. Geye brings to life the details that differ from the sport today. Launching from a platform into the inrun, and throwing one’s arms forward at the takeoff, keeping skis together, rather than forming the V shape my son and his peers strive to perfect. (If, like me, you’re not a jumper, but you’ve been treated to detailed descriptions of jumps while driving your young jumper home from practice, your spidey-senses will alight with every jump described.) One night, feeling nearly breathless from merely reading about the old-style jumps, I wanted to see them. Yet it was late, so I placed my book on the night stand and resisted the temptation of the rabbit hole of potential archival video footage lying in wait on my phone. I made a mental note to do a little digging in between meetings the next day.

The next morning, much like Jon Bargaard, I woke up from dreaming of ski jumping. (Given the absence of jumping in my history, it’s another testament to Geye’s craft.) I started to tell my husband about the book over our first cup of coffee, amidst our son’s predawn hustle to the high school bus. But I’m not really articulate until the end of that cup, beginning of the second—and our conversation at that hour is always punctuated by the last-minute “don’t forget”s and our son reminding us what time he needs to be at training after school, plus The Official Winter Weather Conversation With Teenagers Everywhere: “What about a coat?” Suffice it to say, we didn’t get too deeply into a literary discussion. I never got a chance to talk about the jumping in the book, at all. (I’ll say, here, it’s a very satisfying book to read. Rich in character and story development, and very well paced.)

Twelve hours later, my husband, sitting at his desk in his Park City office and getting ready to pack up for the day, dropped a link into our family group text: “You MUST watch this (I have only seen the first few min) – truly amazing ski jumping stuff in here.” The link was to White Rock, the official documentary film of the 1976 Olympic Winter Games.

When he sent the link, I was, of course, in the process of driving an impromptu ski jumper carpool to give my son’s teammate a ride from their session working on prepping the hills, to the shop where he’d left his car for an oil change. When I checked my phone from the shop parking lot, I grinned and then placed a quick call to my husband. He answered, anticipating my questions.

“First of all, the sport was totally different,” he said, by way of greeting. “You’ll be amazed.”

“Yes! This is what I wanted to tell you over coffee… wait,” I said, interrupting myself. “How did you even find this film?”

“Rick Wakeman did the score,” he said. “I’ve followed him on social media forever, and the algorithms served it up on my feed as one of those, ‘because you follow,’ recommendations.”

“We’ll stream it after dinner in the living room,” I said, absorbing the irony of this 21st Century conversation—about algorithms, streaming content, and a 70s prog rock hero scoring a film that highlights the oldest winter Olympic sport.

(For the uninitiated, Wakeman is a keyboardist and composer who belonged, over several stints, to the band Yes. If you’re interested in more rabbit holes, check out the eponymous album, “Anderson, Bruford, Wakeman, Howe,” a splinter group from Yes that is one of our family favorites.)

Anyway, we watched White Rock after dinner.

The film itself is captivating. Narrated by James Coburn, whose delivery can only be described as “Peak Coburn”. When I exchanged emails with USA Nordic’s Story Project Curator Jeff Hastings last week—after I sent it to him, and insisted he drop everything and watch—he wrote back with an uncanny replica of my husband’s and my summation of the film: “Watching James Coburn play himself is like watching him play any role he ever had… love the quote- ‘… not a jump for glory… a jump for joy.’ Finding this gem was time in the rabbit warren well spent!”

Funnier yet, watching the film inspired me to invent a rabbit warren pop quiz – to find out how many members of my family could name any of the 1976 US delegation in Nordic Combined and Ski Jumping—and every delegation thereafter. I manned the Wiki, and called out names or years. We were abysmal at this game, but we learned a lot. This made a kind note from Walter Malmquist in response to my December 18, 2022 Story Project contribution, all the more fun to receive:

“Wherever we go, there we are. One ski jumping community, steeped in history, friendship, literature, art and, yep, adrenaline.”